Are the holidays over yet? Fifty-five days of fun in ancient Alexandria

I hope you had a good holiday season. This is how many of my emails begin this month. However, the meaning of "holiday season" is slightly elusive. In our society, the festive period typically starts in late November and ends in early January. This doesn’t mean we celebrate non-stop throughout these weeks. The famous English 18th-century carol is more precise, counting exactly the Twelve Days of Christmas, with one gift given each day. It does not, however, account for how quickly supermarkets and retailers pivot to preparing for the next round of holidays—Valentine's Day and Easter.

Important holidays tend to be the longer ones. Ramadan lasts for a month. Easter is celebrated for 50 days in the Catholic Church calendar. The Maha Kumbh Mela festival in northern India stretches over 45 days. In sports contexts, the Olympic Games last two weeks, while the FIFA World Cup spans 29 days.

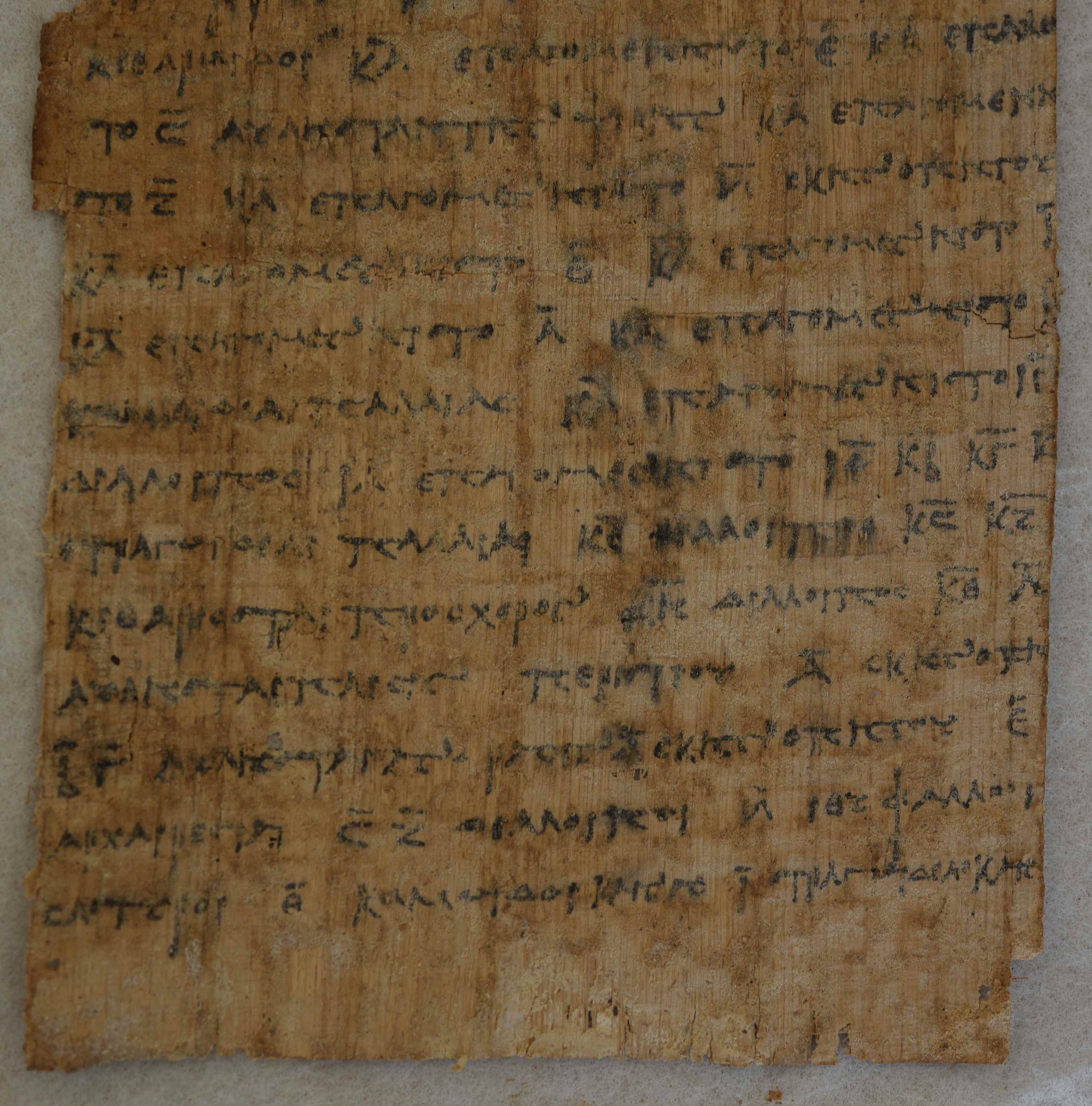

The longest ancient celebration, that is so far known to us, is attested on a papyrus discovered in Egypt in 2020. The text on the papyrus outlines a detailed program for Theadelpheia, a 55-day (!) festival held in Alexandria. For comparison, the ancient Olympic days lasted only five days. The festival's name Theadelpheia refers to Theoi Adelphoi, or "Gods Siblings," in Greek. They were the divine royal couple, the Macedonian king of Egypt Ptolemy II and his spouse Arsinoe who was also his sister. The cult of Theoi Adelphoi aimed to justify (in the eyes of Greeks) their marriage, reminiscent of Game of Thrones.

Ptolemy II and his wife-sister Arsinoe II. Ptolemy I and Berenice I. British Museum

Historians knew little about Theadelpheia — its length, events, or significance to the royal dynasty — until the discovery of this papyrus. Now we know much more. The program, compiled during the reign of Ptolemy III (son of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe), included the birthdays of his wife, Queen Berenice II, and their heir, Ptolemy IV. Most notably, the program featured games, a longstanding accompaniment to religious celebrations in ancient Greece. The Panhellenic games — Olympic, Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian — were widely renowned, but smaller local festivals also included athletic, equestrian, musical, or theatrical contests.

When Alexander the Great occupied Egypt in the 4th century BCE, his successors, the Ptolemaic dynasty, sought to position Alexandria as the cultural capital of the Hellenic world. Lavish games demonstrated the kingdom's power, wealth, and prestige, attracting participants and diplomatic delegations from across the Mediterranean. The Theadelpheia program, as revealed in the papyrus, emulated the finest Greek cultural achievements, such as the Pythian competition in instrumental music and the dramatic festivals of Athens. The festival's theatrical component lasted 28 days, featuring choral dances and performances of classical and new plays, including tragedies, comedies, and satyr dramas. The papyrus presents the first direct evidence of Greek drama being staged in Egypt.

The festival began on the 1st of the Macedonian month Audnaios, which was the heir's birthday. The first week was devoted to preliminary activities, such as participant registration and drawing lots to determine performance order. Curiously, days with no events were listed as “free” — 12 in total. The program becomes perplexing midway: the 21st of Audnaios is repeated 15 times, effectively creating a "Groundhog Day". This provides scholars with evidence that the Ptolemies manipulated the calendar, inserting additional days when needed for festivals. The reason for these 15 extra days remains unknown.

Papyrus program for Theadelpheia from CES RAS excavation. Photo by Elena Chepel 2020.

The version of Theadelpheia documented in the papyrus dates back over 2,200 years to 242 BCE. It is plausible that the festival was preceded by another grand festival, the Ptolemaia, which celebrated King Ptolemy's birthday and the day of his accession to the throne. Like Theadelpheia, Ptolemaia featured competitions and lasted another 55 days. This number is symbolic, reflecting the sacred truce period of the Eleusinian Mysteries in classical Athens, which lasted 55 days to allow safe travel to the city from other parts of Greece, as all military conflicts had to be suspended during this time.

Together, Ptolemaia and Theadelpheia could span over three months in Alexandria. Of course, the intensity of events varied, as indicated by the program, and such festivals were likely held only once every four years. Yet the question remains: what impact did such a lengthy festival have on life in Alexandria?

It undoubtedly left a mark. Alexandrians and foreign visitors enjoyed theatrical performances, while Egyptian priests from across the country gathered to honor the royal couple with rituals. The rural population contributed wine, food, garlands, and sacrificial offerings. One papyrus letter from the period mentions providing pigs for Theadelpheia sacrifices, while another orders to prepare large quantities of old sweet-smelling wine for the birthdays of the King and the Queen. Musicians and athletes from the countryside also likely participated. Around 241 BCE, an aspiring musician named Herakleotes from the Fayum oasis filed a complaint. He was not provided with a proper kithara (ancient harp or lyre) in time for the competition of kithara players, organised by the King, which was part of Theadelpheia’s program. Herakleotes’ papyrus petition implies that musicians started to prepare and train for the festival long in advance.

Kithara-player

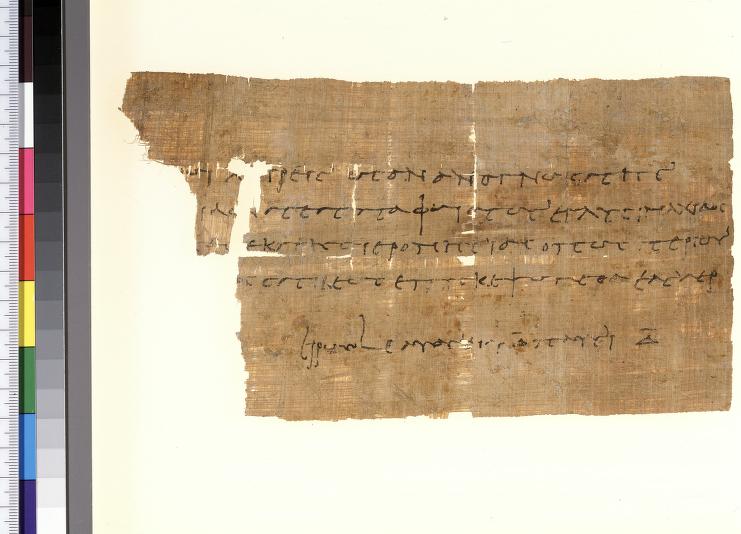

Everyday life in Egypt was also likely disrupted during the festival. Papyrus work contracts often specified that employees were exempt from working on festival days, though not for the entire 55 days. Interruptions extended beyond work. Sacred truce periods during festivals suspended not only warfare but all kinds of violence, including legal punishments. For instance, three papyrus documents from the 210s BCE detail an incident in the Fayum. A fuller named Peteuris accused a local police chief, Tettaphos, of brutally assaulting him and destroying his laundry shop. Peteuris was arrested (no surprise here!) but released shortly after because the incident occurred during a sacred truce. As a reaction to the fuller’s allegation, an official instructed his subordinate to summon Tettaphos for interrogation — after the truce ended. These documents are dated to the month of Audnaios, the same month as Theadelpheia’s sacred truce.

As we can see, over 2,200 years ago, festivals like Theadelpheia were an integral part of life in ancient society, offering both pleasures and challenges.

Order to summon Tettaphos after the holiday (hieromenia). Krokodilopolis, 217 BCE

Below is my translation of the text of the program from ancient Greek.

The festival and the games of the Theadelpheia shall be as follows:

Audnaios, 1: beginning of the sacred truce in the City and Birthday of Ptolemy the son.

2: registration of trumpeters and heralds.

3: registration of horse-breeders, sportsmen, and artists who are going to compete in the musical soloist contest with crown as prize.

4: contest of trumpeters and heralds and registration of the artists who are going to compete in

the musical contests by contract, both choral and dramatic.

5: drawing of lots for the competitions and oath of poets.

6: proagon of choruses of boys.

7: proagon of choruses of men.

8: proagon of tragedies and roll-call of comedians and drawing of lots for those who are going

to compete in the musical contests by contract, which fall into two categories, choral and dramatic,

the latter in turn divided into old and new.

9: Birthday of Queen Berenice.

10, 11, [12, 13,] 14, 15, 16: free days.

17, 18: pulling down of wreaths.

[19:] presentation of poets and drawing of lots of venues.

20: … horse race and … soloist and drawing of lots for those who are going to

compete in the musical soloist contest.

21: horse race and pentathlon.

Intercalated 21, 2nd intercalated 21: kitharists – solo music.

3rd intercalated 21, 4th intercalated 21: kitharodes.

5th intercalated 21, 6th intercalated 21: aulos-players – solo music.

7th intercalated 21, 8th intercalated 21: setting up the stage.

9th intercalated 21, 10th intercalated 21, 11th intercalated 21, 12th intercalated 21: old comedies.

13th intercalated 21: free day.

14th intercalated 21, 15th intercalated 21, 22, 23, 24: old tragedies.

25: free day.

26, 27: kitharists – choral contest.

28: free day.

29, 30: choruses of boys with aulos-players.

Peritios, 1: setting up the stage.

2, 3: choruses of men with aulos-players.

4: setting up the stage.

5: elections of magistrates.

6, 7: free days.

8: performances of ithyphalloi and satyr-plays.

9: comedians – new [comedies].

10: new tragedies.

Full edition can be consulted in Elena Chepel, A New Papyrus Programme for the Theadelpheia: Ptolemaic Festival Culture and Dynastic Ideology. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 222 (2022), 159–178.