To Abydos and Back Again: Graffiti, Festivals, and Travel in Ancient Egypt

Temple of Seti I at Abydos. Photo E. Chepel

Three weeks ago, I visited Abydos for the first time — a place that has captivated travellers for thousands of years. As one of the most significant religious centres of ancient Egypt, Abydos was renowned for its cult of Osiris, the god of death and rebirth. The earliest temples here date back nearly 5,000 years, and worship continued at the site until at least the 4th century CE. Later, as often happened in Egypt, a Christian monastery took over the sacred ground.

Today, the main attraction for visitors is the stunning Temple of Seti I. Everything about it is breathtaking — the architecture, the interplay of light and shadow, and, most of all, the intricate reliefs and hieroglyphs that cover its walls. It’s easy to imagine that ancient travellers were just as awestruck as I was, which might explain why so many left their mark — literally. They carved their names into the temple walls, ensuring their pilgrimage would be remembered and securing the blessing of the gods.

The aim of my recent trip to Abydos was to see and study these inscriptions – graffiti – firsthand. We often see graffiti as vandalism or a controversial act of self-expression. But for the study of the ancient world, graffiti are something different — an invaluable historical record. These markings provide evidence of pilgrimage, cross-cultural encounters, and the lives of ordinary people who travelled to this sacred site.

Dr. Mohamed Abuel-Yazid kindly showing us the site. Photo I. Rutherford

Inside the temple, more than 800 ancient graffiti remain, spanning over a thousand years — from the 6th century BCE to the 4th century CE. Together with Ian Rutherford, a leading expert on ancient pilgrimage and an international partner on my research project, we explored every corner of the temple, carefully examining these inscriptions. What we found was remarkable: layered, multilingual messages left by visitors over centuries.

These inscriptions appear in Greek, Hieratic Egyptian, Carian, Cypriot, Aramaic, Phoenician, Coptic, and later Arabic, written in the spaces between the hieroglyphs. Their presence shows just how many different cultural and religious groups were drawn to Abydos. Most graffiti follow a simple formula: the traveler’s name, their father’s name, and sometimes their place of origin. Some also include dates, particularly referencing the month of Khoiak — the time of the great festival of Osiris, which is vividly depicted on the temple’s walls.

Graffito of Sarapion, with the date: 10th year of Claudius, Khoiak 11 = December 7, 48 CE. Photo E. Chepel

Who Were These Travellers?

It’s likely that many of the graffiti writers came to Abydos specifically for the Osiris festival. Most were from the cities in Upper and Middle Egypt. Some were mercenaries from Crete, Cyprus, and other Mediterranean regions, stationed at military camps nearby. Surprisingly, only two graffiti have been identified as coming from visitors from Alexandria, the capital of Egypt during the Greco-Roman period.

Graffito of Demetria and an Alexandrian Zenon, son of Gordios. Photo E. Chepel

Many travellers arrived with their families, bringing wives and children along. Women also left graffiti on their own, an intriguing sign of their independent participation in pilgrimage. Numerous inscriptions contain the Greek word proskunema — meaning “act of devotion”. This word comes from proskuneo, meaning to bow down or prostrate oneself before a god or ruler. It suggests that these travellers viewed their visit as a deeply religious experience.

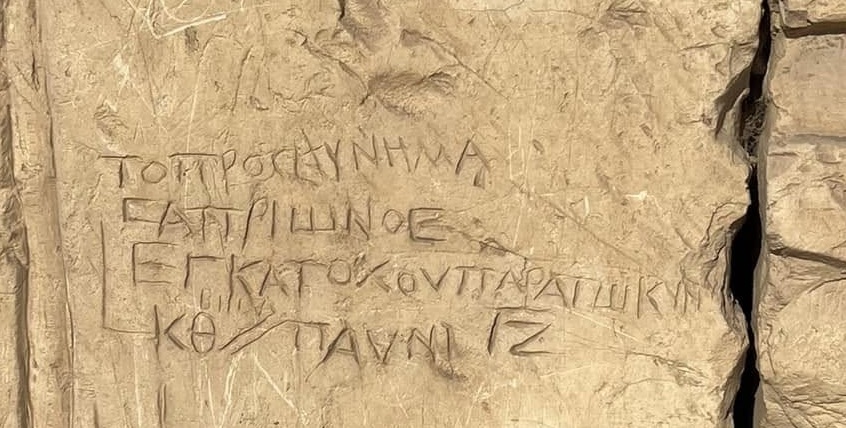

One fascinating tradition involved writing not only one’s own name but also those of family members who had stayed behind. A graffito left by a man named Sarapion, for example, records his proskunema for his mother, Irene, and “everyone at home”. Another common phrase found in graffiti is ἥκω — meaning “I have come” — a simple but powerful statement of physical presence and sense of achievement.

A graffito starting with the word proskunema (ΤΟ ΠΡΟCΚΥΝΗΜΑ). Photo E. Chepel

Journeys to the Festival

What was it like to travel to Abydos for these festivals? The ancient historian Herodotus describes festival journeys to Bubastis, a city in the Nile Delta, as lively, music-filled celebrations:

“Men and women travel together by boat, making music, singing, and clapping their hands. When they pass by a town, some mock the women onshore, others dance, and some expose themselves. But when they arrive, they celebrate with great feasts, drinking more wine than during the rest of the year combined.”

This paints a vivid picture, but the reality was probably far less glamorous. Letters preserved on papyrus show that travel for religious festivals was often routine and practical. In one letter from the 3rd or 4th century CE, a man named Petosiris writes to a woman, likely his wife, arranging her journey:

“Greeting, my dear Serenia, from Petosiris. Be sure to come up on the 20th for the god’s birthday festival. Let me know whether you are coming by boat or by donkey, so we can prepare accordingly. Take care not to forget. I pray for your continued health.”

Not exactly a wild party — but an insight into the logistics of festival travel in the ancient world.

Donkeys seem to still be in use at Abydos. Photo E. Chepel

A Temple of Champions

In Roman times, the Temple of Seti I was not only a pilgrimage site but also home to the oracle of Osiris-Serapis, and later of the Egyptian god Bes. This oracle was particularly popular with athletes, who sought divine guidance on their chances of victory in competitions. Some, after winning, returned to Abydos to leave inscriptions of thanks.

On the temple’s outer walls, several graffiti celebrate sporting achievements. One, left by an Olympic champion named Anubion, is even decorated with a wreath. Athletes who had triumphed in the Pythian Games also left inscriptions, sometimes with drawings of laurels or figures in victory poses. Interestingly, these winners most probably had not competed in Greece, as Egypt hosted its own prestigious athletic contests, which were recognised as equal to the Olympics or the Pythian Games in Delphi.

A scratched drawing of an athlete as part of champions' graffiti. Photo E. Chepel

Leaving a Mark on History

These ancient graffiti tell a deeply human story — of devotion, travel, and the desire to be remembered. They reveal connections between cultures, between past and present, and between everyday people and the divine. Standing in the temple of Seti I, reading the inscriptions left by those who stood there centuries before me, I felt a profound sense of continuity. Abydos was not just a place of worship — it was a meeting point of worlds, where travellers sought blessings, shared their presence, and inscribed their names into history itself.