Time Off for the Gods: Festival Mobility in Graeco-Roman Egypt

On March, 20, I presented my research on festival mobility in Graeco-Roman Egypt at the Research Seminar of the Department of Classics at the University of Reading. My paper, chaired by Prof. Ian Rutherford, explored new evidence of religious travel to Abydos, contextualising it within papyrological and literary sources.

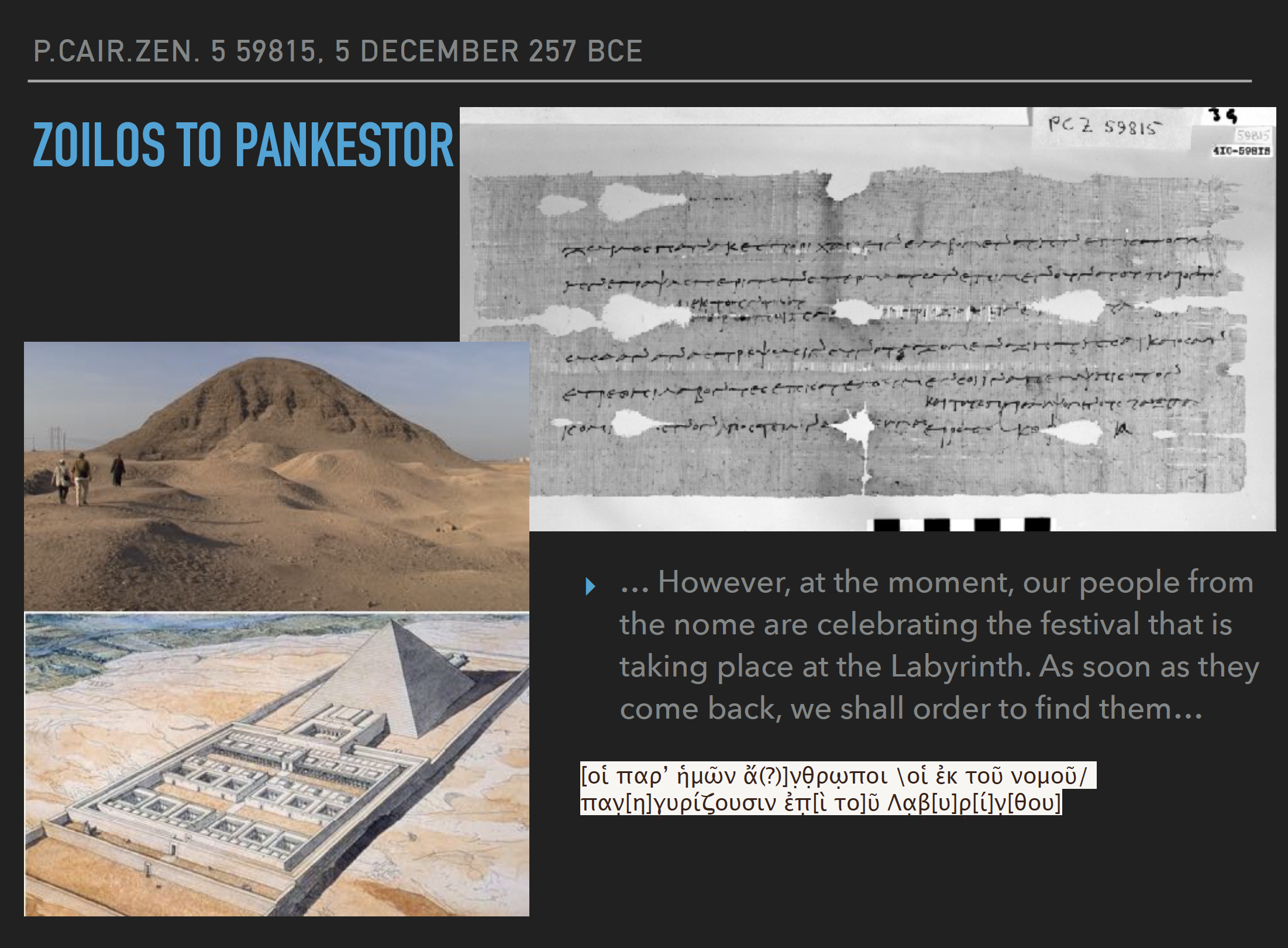

Among papyrus documents, I discussed a business letter from the Zenon archive, which reports that local workers were absent due to a religious festival at the Labyrinth. This site, located in Hawara in the Fayum, was actually a mortuary temple of Pharaoh Amenemhat III, similar to the Temple of Seti I in Abydos. It was visited already by Herodotus, who admired it even more than the Great Pyramids of Giza.

Herodotus' account of the Labyrinth:

I have seen it myself, and indeed words cannot describe it; if one were to collect the walls and evidence of other efforts of the Greeks, the sum would not amount to the labor and cost of this labyrinth. … Though the pyramids beggar description and each one of them is a match for many great monuments built by Greeks, this maze surpasses even the pyramids. It has twelve roofed courts with doors facing each other: six face north and six south, in two continuous lines, all within one outer wall. There are also double sets of chambers, three thousand altogether, fifteen hundred above and the same number under ground. We ourselves viewed those that are above ground, and speak of what we have seen, but we learned through conversation about the underground chambers; the Egyptian caretakers would by no means show them, as they were, they said, the burial vaults of the kings who first built this labyrinth, and of the sacred crocodiles. Thus we can only speak from hearsay of the lower chambers; the upper we saw for ourselves, and they are creations greater than human. The exits of the chambers and the mazy passages hither and thither through the courts were an unending marvel to us as we passed from court to apartment and from apartment to colonnade, from colonnades again to more chambers and then into yet more courts. Over all this is a roof, made of stone like the walls, and the walls are covered with cut figures, and every court is set around with pillars of white stone very precisely fitted together. Near the corner where the labyrinth ends stands a pyramid two hundred and forty feet high, on which great figures are cut. A passage to this has been made underground (Transl. A. D. Godley).

Work contracts from the Roman period indicate that workers had days off during important holidays. One apprenticeship contract from Oxyrhynchus specifies that the apprentice was entitled to seven days off for the Amesysia, a festival celebrating the birthday of the goddess Isis. This festival was perhaps one of the most significant in Oxyrhynchus.

Another apprenticeship document, known to papyrologists as the Heidelberg Festival Papyrus, records the occasions when a boy was absent from work. Some of these absences appear to be for festivals celebrated in Upper Egypt – in Abydos, Ombos, Koptos, and Dendera, where the apprentice traveled with his mother for a day.

The Hathor temple at Dendera

Dendera was the major cultic centre of the goddess Hathor in Egypt. Its temple was rebuilt during the late Ptolemaic and early Roman periods and hosted an annual festival known as the Beautiful Reunion, which celebrated the union of Hathor with her divine husband, Horus, who resided upstream in the temple at Edfu. Juvenal’s Fifteenth Satire, which describes the rivalry between Dendera and Ombos over their gods, may reflect the reality of people traveling to festivals at neighboring temples in Upper Egypt:

Between the neighbours Ombi and Tentyra there still blazes a lasting and ancient feud, an undying hatred, a wound that can never be healed. On each side, the height of mob fury arises because each place detests the gods of their neighbours. They think that only the gods they themselves worship should be counted as gods. So when one of these tribes was holding a religious festival, the chieftains and leaders of their enemy decided unanimously to seize the opportunity to prevent them from enjoying a happy and cheerful day and the pleasures of a great meal: the tables set up at the temples and crossroads and the sleepless dining couches, night and day, which sometimes lie there until the seventh dawn finds them. (Transl. G. G. Ramsay)

Papyri and other sources reveal that festival travel was an important devotional practice in Graeco-Roman Egypt, as employers adjusted work conditions to accommodate it. It was also a personal religious custom – something individuals chose to do rather than an event organised by the authorities on their behalf.

Festival mobility was thus part of lived religion – a form of religious experience integrated into people’s life and an activity that expressed individual religious agency.

Inside the Hathor temple at Dendera